The Russian Revolution of 1917 saw the end of the tsarist empire and the rise of a communist regime: the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In territorial terms, the USSR was an empire of its own, covering at its height nearly one-sixth of the Earth’s surface—two and a half times the size of the United States. Before the USSR’s dissolution in 1991, this vast expanse of land stretched from the Balkans to the Bering Strait, counting China, Iran, and Finland among its neighbors. With over 100 different nationalities living within Soviet borders, the centralized government sought a new visual vocabulary that could unite its diverse people.

So, starting shortly after the revolution, and particularly after Joseph Stalin came to power in the late 1920s, architecture was increasingly called upon to reinforce Soviet rhetoric and collective identity throughout the realm. Monumentality, industrial motifs, and a strained blending of classicism and modernism were at the heart of a broad range of Soviet architectural projects, which captured the creativity of their architects but also the state’s centralized message. Below, we look at several of these iconic Soviet structures, from skyscrapers to workers’ clubs to an unbuilt ode to Marx.

Melnikov House, Moscow

ARCHITECT: KONSTANTIN MELNIKOV

Photos by Alex ‘Florstein’ Fedorov, via Wikimedia Commons.

Inspired by his country’s blunt dismissal of tradition, architect Konstantin Melnikov became a pioneer of the avant-garde, designing dynamic, modular buildings that captured the spirit of the emerging Soviet state. The house he built for himself in 1929 is a prime example. Possibly the most innovative structure of his career, the Melnikov House consists of two interconnected cylinders pierced with hexagonal windows. Each cylinder is three stories high, allowing for both studio and living space in a modernist form that feels like a breath of fresh air amid the ubiquitous nondescript blocks popular in the Soviet era. Melnikov believed the cylinder shape to be an economical solution to strict construction rations imposed on architects by the state; true to his design, the form was able to maximize the structural potency of such limited materials. Surprisingly, a city planning committee—which prized uniformity above all else—approved Melnikov’s groundbreaking design, affirming his undeniable ingenuity.

Rusakov Workers’ Club, Moscow

ARCHITECT: KONSTANTIN MELNIKOV

Photo by Branson DeCou, via Wikimedia Commons.

As the Soviet Union sought to cultivate a collective identity, workers’ clubs became cultural hubs for the proletariat. Reversing the traditional notion that clubs should be private and only serve noblemen or the bourgeoisie, these clubs were places where workers of all ages could come together to relax and participate in leisure activities, typically in spaces run by trade unions or political organizations. At the Rusakov Workers’ Club, for instance, trolley workers could socialize within a massive fan-shaped edifice, another of Melnikov’s designs. Built between 1927 and 1928, the “tensed muscle,” as Melnikov called it, was a nod to the building’s function as a center for the working-class as well as a reference to the flexibility of its architecture. Protruding from the building’s core are three cantilevered seating areas, which can be used as separate auditoriums or, when combined, seat up to 1,400 people.

Zuev Workers’ Club, Moscow

ARCHITECT: ILYA GOLOSOV

Photo by Branson DeCou, via Wikimedia Commons.

This building, another workers’ club, was designed by Constructivistarchitect Ilya Golosov in 1926. Completed in 1928, the building incorporates several Constructivist principles, including its clearly delineated geometry and an embrace of advances in technology and engineering. The building is anchored by a glazed cylinder crisscrossed with a perpendicular plane, which hides a grand staircase. The relationship between the roundness of the cylinder and the sharpness of the angular elements gives the structure a dynamic quality evocative of the paintings of fellow Constructivists like El Lissitzky. Inside, several meeting rooms and an 850-seat theater served as spaces for education, entertainment, and assemblies. Even today, the Zuev Workers’ Club retains its original function as a cultural center, serving as home to a children’s and comic theater.

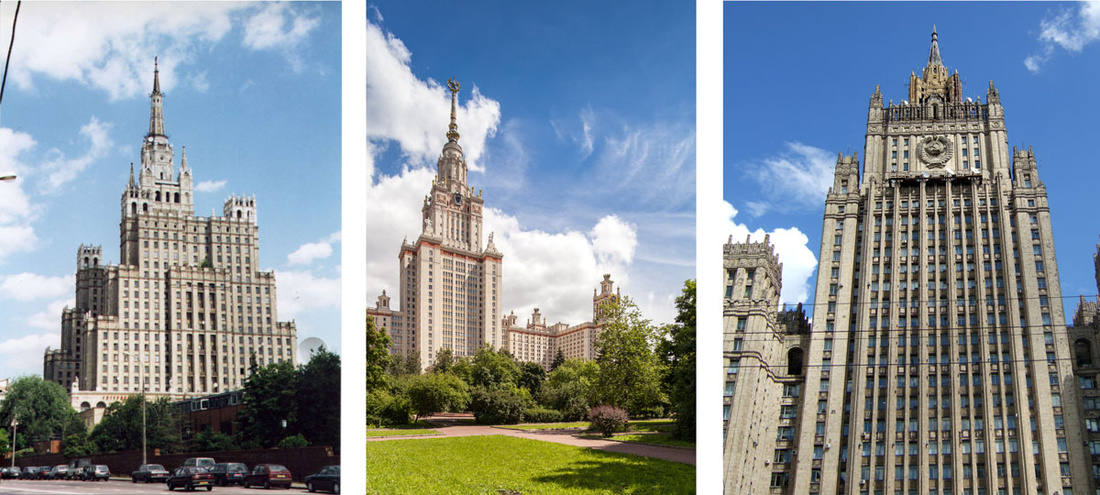

Seven Sisters, Moscow

ARCHITECTS: VLADIMIR GELFREIKH, ARKADY MORDVINOV, M. A. MINKUS, LEV RUDNEV, VYACHESLAV OLTARZHEVSKY, LEONID POLYAKOV, DMITRY CHECHYLIN, ANDREI ROSTKOVSKY, ASHOT MNDOYANTS, MIKHAIL V. POSOKHIN

Left: Kudrinskaya Square Building. Photo by Jamie Barras, via Flickr; Center: Moscow State University. Photo by Sergey Norin, via Flickr; Right: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Photo by Gioconda Beekman, via Flickr.

These seven skyscrapers still loom over the Moscow skyline, leading some to see them as grim reminders of the repressive Stalinist regime during which they were built. Indeed, Stalin himself took a personal interest in the project. Fearing that Westerners would look down on Moscow for its lack of modern European amenities, he called upon some of the region’s top architects to erect eight ornate, monumental skyscrapers, which have since become synonymous with Russian architecture under the totalitarian leader. The seventh “sister” was completed in 1957, four years after Stalin’s death, signaling the end of the Baroque-meets-Gothic architectural style promoted by the state under his control. Though the eighth skyscraper was never built—the soft soil of the Moskva riverbank, coupled with a shortage of resources, caused the project to be axed—the sisters’ signature spires continue to soar above the city today.

Central Research Institute of Robotics and Technical Cybernetics, Saint Petersburg

ARCHITECTS: B. I. ARTIUSHIN AND S. V. SAVIN

Photo via Wikimapia.

The Central Research Institute of Robotics and Technical Cybernetics—changed to Saint Petersburg State Polytechnic University in 1981—stands in sharp contrast to the dreary brutalism often associated with Soviet architecture. Rather than the harsh totalitarianism of the Soviet Union’s communist government, this “white tulip” building represents the pioneering spirit of the space race. The complex was indeed designed as a center for robotics engineering and the development of space technologies. Its space-age style can be seen as a reference to the USSR’s isolation during the mid-20th century, when, as if existing on its own planet, the state blocked itself off from the rest of the world.

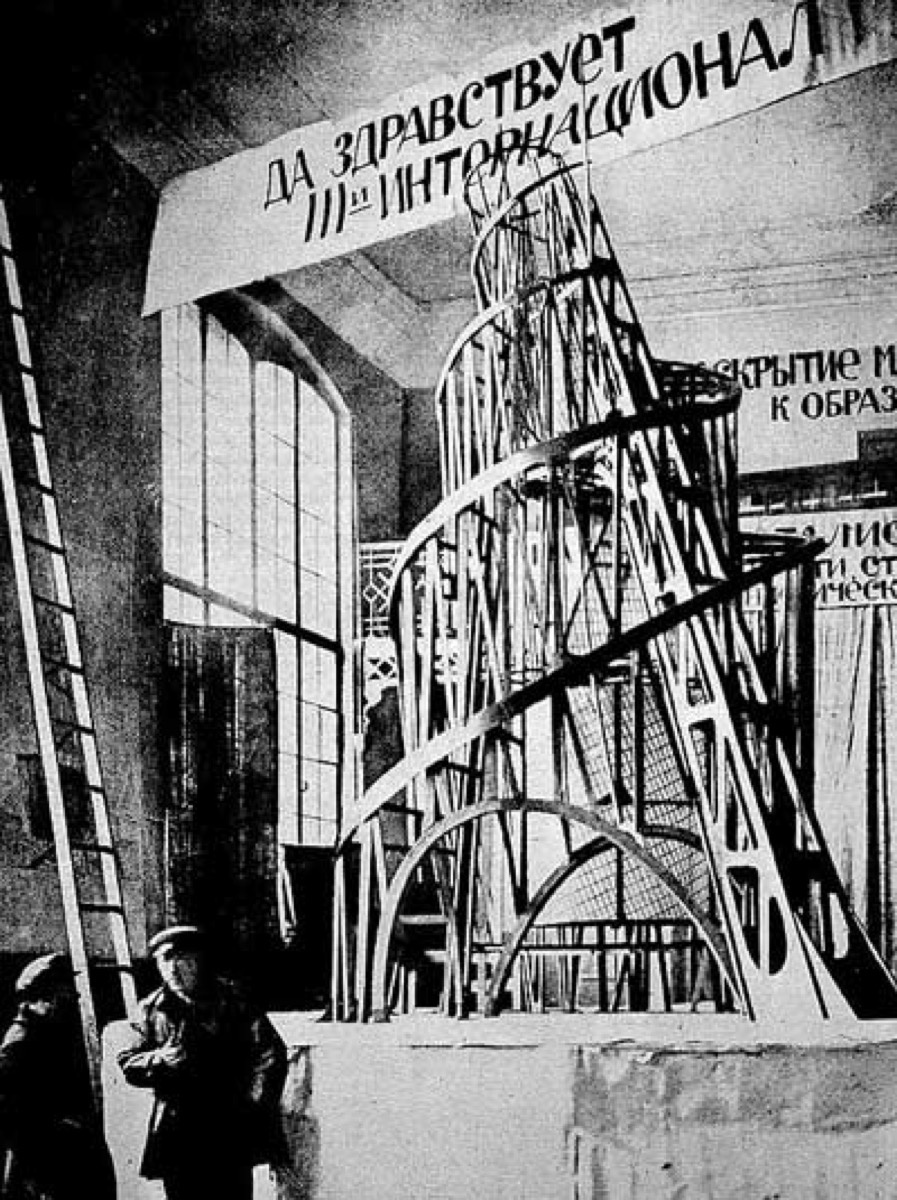

Monument to the Third International, intended for Saint Petersburg

ARCHITECT: VLADIMIR TATLIN

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Had it been built, Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International would have been the greatest physical manifestation of Vladimir Lenin’s “Monumental Propaganda” initiative. As the head of this program, Tatlin took on the task of replacing tsarist monuments with those that reflected the ideals of the Bolshevik Revolution and the new regime that followed. His monument was envisioned as the headquarters for the Third International, an international association of communist organizations meant to spread the revolution around the world. Tatlin proposed that the abstract tower of iron and glass be 1,300 feet tall, surpassing the Eiffel Tower by about 300 feet. Beyond its sheer size, the structure’s ideological symbolism would have been crucial. The spiral shape referenced Marx’s dialectical materialism, while the tower’s tilt was meant to mimic that of the Earth, thus pointing the edifice at the North Star.

The House of Soviets, Kaliningrad

ARCHITECT: YULIAN L. SHVARTSBREIM

Photo by Maarten, via Flickr.

Like Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, the House of Soviets was also designed to take the place of a former seat of the monarchy—in this case, Königsberg Castle in what had once been East Prussia. The castle suffered extensive damage after being bombed during World War II, so when Kaliningrad was absorbed into the USSR after the war, the Soviets used the opportunity to transform the site into an administration building for the region. Originally, in the 1960s, the building was planned to be 28 stories tall, though its weak foundations only allowed for 21. Further construction woes forced construction to a halt in 1985, with the building still unfinished; today, the House of the Soviets is just an empty shell, having never been completed or put to use. Locals endearingly refer to it as “the buried robot,” a reference to its rectilinear form and mechanical visage.

—Nora Landes

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario